- The Temptations Band History - August 26, 2022

- Roy Orbison Bio - August 9, 2022

- Elton John Bio: The Story of an Icon - July 31, 2022

David Bowie’s Aesthetics Didn’t Exist In A Vacuum

David Bowie had an aesthetic in the way that the Louvre has a painting. Yes, it’s technically true, but it does not elucidate the statement’s scope. David Bowie is known for his reinvention, both his music and his personal style that accompanied the change in sound.

His educational background in multiple media (music, theatre, mime, visual art, design, etc) signifies that we can’t separate Bowie’s different hats from the different media he wore them in. The whole image/sound of Bowie in each period must be considered at once.

Background

Bowie went to Bromley Technical High School, which was as eccentric as the artist Bowie would come to be. The school operated with a “collegiate atmosphere,” allowing Bowie to specialize in his education rather than the broad strokes of the usual bastions of primary education (math, science, history). Post-graduation, he continued his education in the arts, formally and informally.

After a lackluster debut album, Bowie took some time away from music to study the dramatic arts with Lindsay Kemp. This education would lead to an artistic collective of sorts, “Feathers,” a group that performed a balanced set of music, poetry, and mime. Over the next few years, while returning to music, he would continue to collaborate with other artists across multiple media.

Earliest Aesthetics

From the earliest parts of his career, Bowie was cognizant of the necessity for a brand (though perhaps not in the extremely corporate sense that we use ‘brand’ in the 21st-century). A perfect example is the discarding of his birth name, ‘David Jones’, in the mid-60s.

The switch, I don’t think, was purely an effort to separate himself from the similarly-named artist of ‘The Monkees’ fame. The inspiration for ‘Bowie’ was the fighting knife named for 19th-century American James Bowie.

Bowie could have chosen from a plethora of standard names or even simply changed his first name and kept his surname ‘Jones.’ Still, Bowie had a sharper wit (pun intended). Take a moment to consider the word association and imagery that arises when thinking about knives.

Your mind probably conjured words like ‘sharp,’ ‘dangerous,’ ‘violent,’ or perhaps it imagined scenarios of a knife being used. Whether your mind took a PG route or an NC17 route, you imagined how a knife tears and cuts in an inherently violent manner. Now, consider these thoughts being attributed to a performer. You’re already more intrigued, aren’t you?

The evolution in album art for his first two albums showcases Bowie’s understanding of how image relates to sound and the importance of leveraging that correlation.

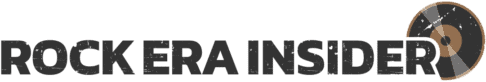

The first album represents a toned-down, family-friendly artist. Straight, neatly-cropped hair on a well-lit subject who leans from left to right across the frame. He is homogenous and indistinguishable from the other artists that he wishes to emulate of the day. Frank Sinatra and Bill Evans may have been enigmatic performers, but they were “safe” artists, free of controversy (or famous enough that any dark side was kept hidden away).

While his first album would ultimately flop, the album art remains open to the sensibilities of the conservative audiences/sociopolitical tone of the pre-hippie era. It captures the sound that he was going for: “theatrical character sketches, often from a childlike lyrical perspective, delivered in an overenunciating voice”.

This is the album art to match the music of an artist who is trying desperately to be taken seriously, utilizing easy-listening and safe genres (even if the lyrics sometimes stray from that aesthetic).

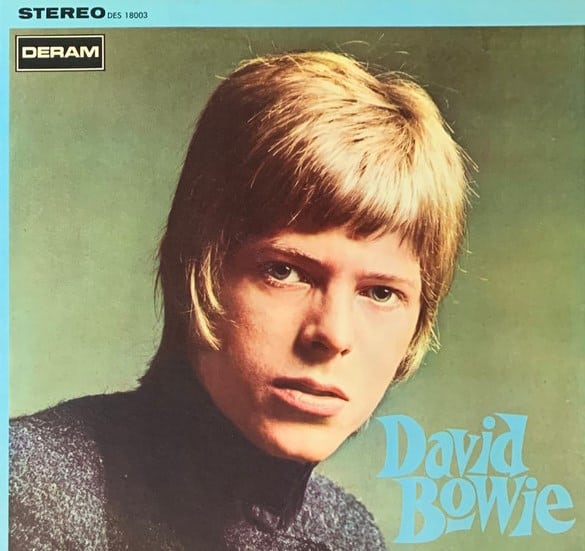

In just two years, David Bowie reclaimed his very own name. The album art makes as bold a statement as the psychedelic genre itself, a genre that begs for a change in state (ie, getting high) to fully appreciate it. Like other psychedelic artists, the album art itself almost serves as a warning “This isn’t your parents’ music”.

Ssssh features frenetic songs with lyrics hinting at depraved attitudes towards sex and innocence. The soundscape of Dark Side of the Moon leaves no mistake about the influence of psychedelics. Likewise, David Bowie’s (second) album is far more psychedelic, soaked in reverb. The lyrics are darker and more sinister.

Gone is the balanced lighting and the casual stance of a serious man. His head is disembodied, half-cast in shadow, and suspended in the very center of the frame. The slight gradient of the color (both the background and grid of circles) hijacks your focus, pushing it inwards.

The hair is no longer neatly trimmed but tousled and wild (yet still perfectly symmetrical). The slightly ajar mouth and face parallel with the frame gives off the aura of a predator, ready to strike.

From his (second) self-titled album through The Man Who Sold the World, his personal style continued to evolve. The Hype (a band briefly formed following his 1969 release) wore bombastic pre-glam outfits on stage, foretelling the coming of Ziggy Stardust.

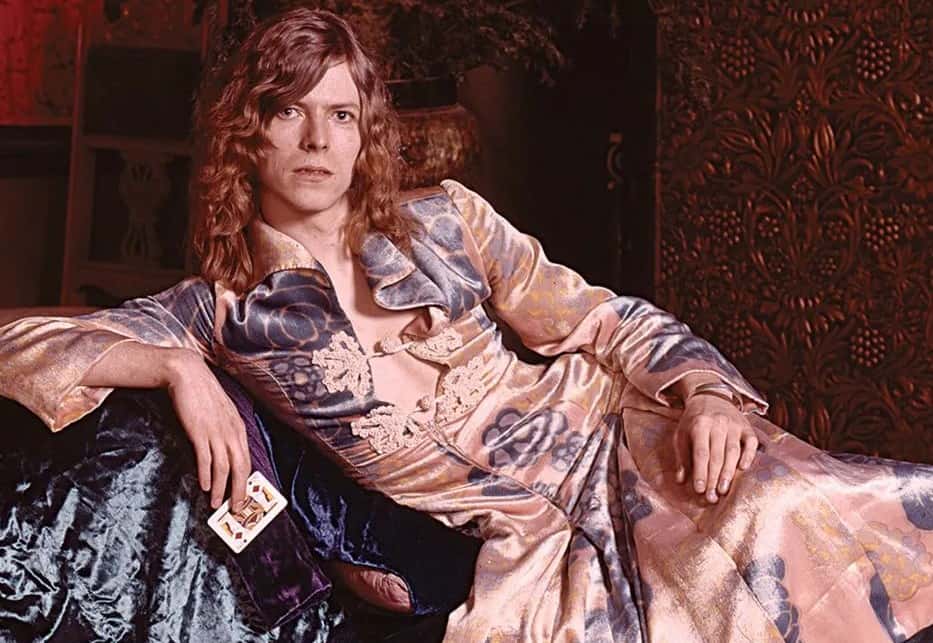

David Bowie embraced his crossdressing (The Man Who Sold the World art featured Bowie in a full-body dress). Again with Hunky Dory, Bowie matched the softer art-pop and melodic rock with a softer, more sensitive, feminine aesthetic.

Ziggy Stardust – Halloween Jack

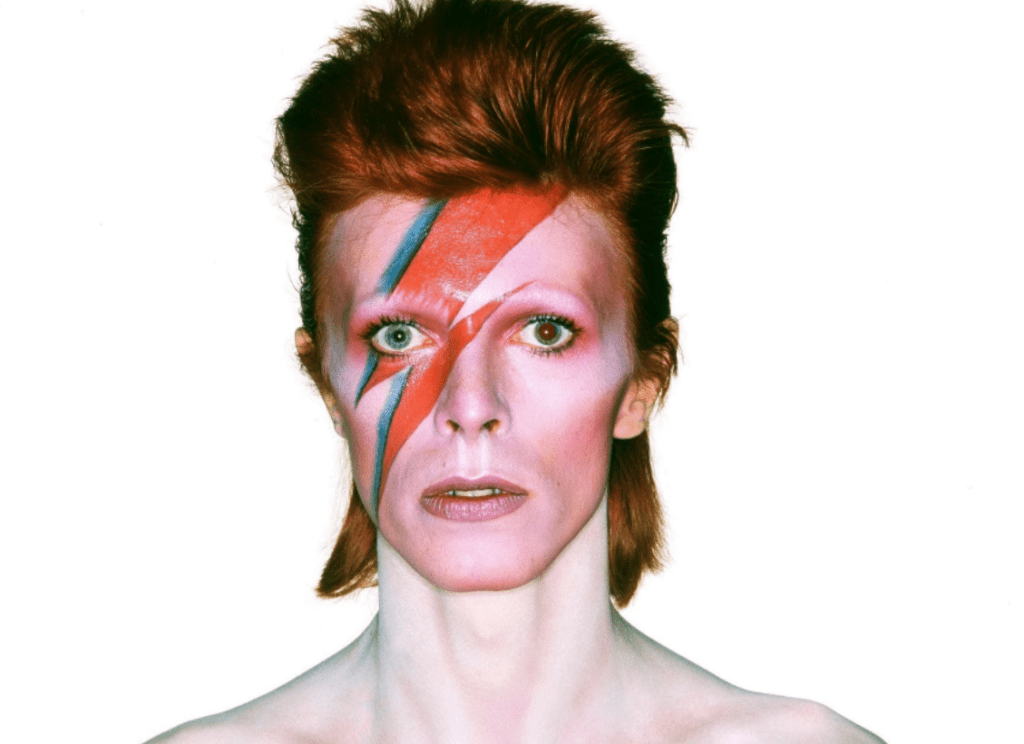

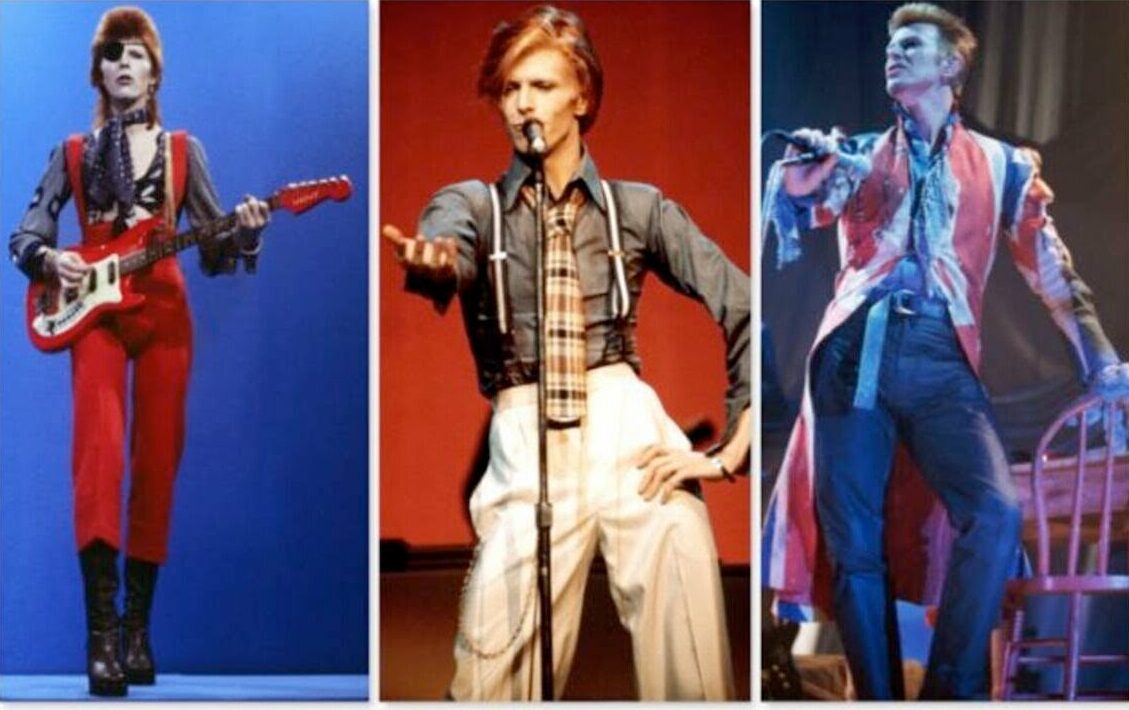

Ziggy Stardust is probably the most famous of David Bowie’s personas. Lyrically, the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars tells the story of an alien falling to Earth with a message of hope five years before its end and the accompanying Bacchanalian journey through excess and delusion in that time.

So, naturally, David Bowie embraced the excess and Bacchanalia into an elaborate, full-glam outfit complete with spikey, fire-engine-red hair and a gold astral sphere on their forehead designed by Freddie Burretti and Pierre Laroche, respectively. Furthermore, the stage shows of the Ziggy Stardust were known to be equivalently outrageous.

Bowie’s backing band wore equally glamorous costumes and stage make-up, and the performances were rounded out with insane showmanship and choreography. Again, Bowie understood the importance of consistency across multiple media at once.

Similar to Ziggy, but not quite the same was Aladdin Sane. Aladdin Sane was described as “Ziggy goes to America,” fitting considering that most of the album was written while on tour in America.

The slightly grittier aesthetic matches the despondent lyrical content of the corresponding album: the dark side and price of stardom (sex, drugs, & rock n’ roll) as well as reflections of the decay and violence of urban America.

Beyond the lyrics, the music of this album is often unsettled (eg the helter-skelter piano of the title track). The name of Aladdin Sane is itself a pun reflecting the mental state of Bowie (= ‘a lad insane’).

The last of Bowie’s glam personas was Halloween Jack from the 1974 album Diamond Dogs. While this glam persona was also retired after just one album, the slight variances were an important piece to the album aesthetic.

As much of the lyrical content is adopted from Orwell’s novel 1984, I believe the adoption of the eyepatch was a happy accident to relate to the themes of being watched by ‘Big Brother’ and a correlation to the violence caused by an oppressive, authoritarian regime.

Soul Man – The Thin White Duke

As Bowie’s Diamond Dogs tour began to transition into the soul/funk sound that would dominate the next couple of albums, Bowie changed his appearance with it. While I would argue that most everything that David Bowie did was cool, Young Americans was a record that was designed to be “cool,” and, thus, Bowie’s style needed to reflect that.

Gone were the histrionic one-piece costumes and the aureate make-up. They were replaced by sleek, fitting, single-color suits and perfectly slicked-back hair with just the right shades of gold and marmalade. The look was a number of steps lowered in tone(placeholder) from the previous three aesthetics, but no less a piece of art.

And unsurprisingly, the music matched the aesthetic. The ‘cool’ took hold in America, and Bowie found himself holding his first number 1 single, the aptly named “Fame”. The album took inspiration from black artists (which isn’t to dismiss that rock n’ roll and blues have their roots in black music, too) whose genres always seem to be ahead of the curve (placeholder), i.e.) cool.

Thanks to his genuine care in doing right by the genres and the communities that produce them and his vocality in advocating for them, David Bowie was one of the first white artists to appear on Soul Train.

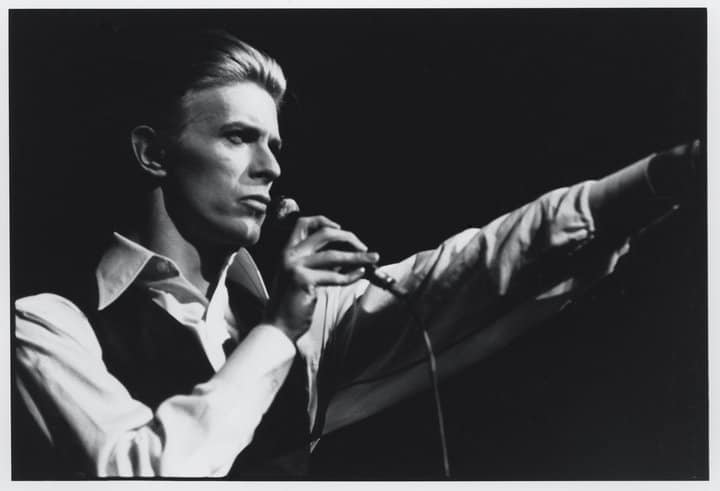

The Thin White Duke is, in my opinion, the scariest of David Bowie’s personas. It is also the persona that most captures all of Bowie (at that particular snapshot in time). In 1976, The Man Who Fell To Earth was released, a feature-length sci-fi film in which David Bowie had his first starring role.

Bowie played Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who arrives on Earth searching for relief from Earth’s waters for his drought-stricken planet. His character amasses a great deal of money and power in his pursuit to return home and is rather despondent and aloof to the needs and desires of humans.

The mid-70s for Bowie were marred by a debilitating cocaine addiction. The excessive use would warp Bowie’s mental state, pushing him dangerously close to the edge of schizophrenia (a disease that ran rampant through his mother’s side of the family, ultimately claiming his half-brother’s (Terry Burns) life through suicide). The warping of the mind also twisted Bowie’s political sensibilities, leading him to be very vocal in supporting fascism.

Bowie plays an alien who is separated emotionally from the people on the planet he resides on, while his real-life persona advocates for a system of government that is “characterized by dictatorial power, forcible suppression of opposition, and strong regimentation of society and the economy.”*, i.e.) separated emotionally from the people of the country.

Meanwhile, the 1976 album Station to Station features lyrical themes of the conflict between yearning for connection and the safety of being isolated. Again, the theme of “isolation” and “distance” plays into Bowie’s aesthetic.

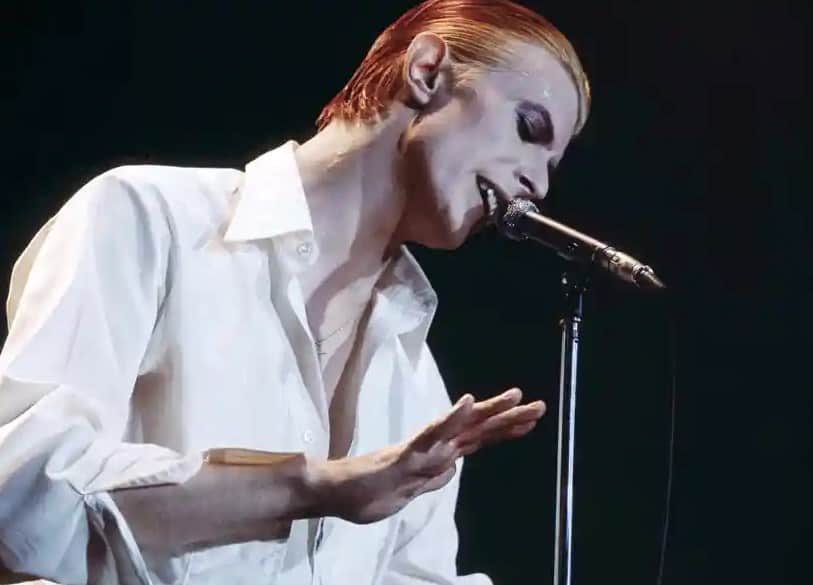

As for the visual aesthetic, Bowie’s clothes are simple but sharp and diligently cut. He wears black pants and a vest and a white buttondown. He often completed the ensemble with heavily-greased back hair for a macho-Aryan look. The look is partly adopted from his costumes in The Man Who Fell To Earth.

But the gaunt appearance and thin frame, while a result of heavy cocaine use, gives you the idea that the isolation and despondence might just cause Bowie to fade away and disappear from view altogether.

*As much as I am a Bowie fanboy, I’m not defending this aspect of his life. Nor am I trying to play off his support for fascism as simply a controversial, 4D chess move to push his own brand. I condemn fascism, and the violence needed to instill it. In the context of Bowie committing to aesthetics, I simply find the coincidence interesting.

Berlin Trilogy

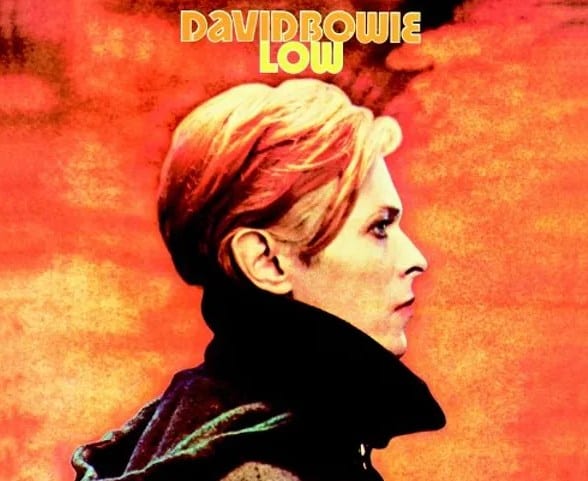

While these three albums would prove to be a cornerstone of his catalog, the lack of an aesthetic statement here is the aesthetic. While Bowie wouldn’t retreat to sweatpants and New Balances, there was no grand, overarching character or persona that would encapsulate this time period.

Low reuses a still from The Man Who Fell to Earth as the album art. The Heroes album art places more emphasis on the implied movement of Bowie’s arms and frame than on any particular fashion choice (though that leather jacket and hair-quaff is fire…), and (the main album art for) Lodger completely cuts off all of Bowie except for the legs below the knees.

The time spent in Berlin was a time of refocusing. He utilized the time and new environment to sober up and explore Berlin’s growing (commercial) music scene. Bowie also utilized these three albums as a chance to explore with acclaimed producer Brian Eno to explore ambient music.

While the single Heroes is Bowie’s best anthem*, these 3 albums were generally marked by their quiet space between the music notes, as Debussy would say (albeit with a different intention). Even the album titles are but one word apiece.

*if you disagree, fight me

The 80s

In the 1980s, Bowie returned to the mainstream, casting off the ambient and avant-garde of the Berlin trilogy. His first album and corresponding single in the 1980s would hit number 1.

Furthermore, Bowie would mark his return by embracing a movement that was initially inspired by his Ziggy Stardust persona (the period of his life where he initially exploded commercially), the New Romantic.

Both his style in this time and the music were reminiscent of an earlier period in his life. The style would return to bombastic outfits and make-up of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane. The songs themselves would also beckon back to his early career.

Ashes to Ashes tells an ‘updated’ story of astronaut Major Tom from the 1969 single, ‘Space Oddity’. While 1977 wasn’t as far off as 1969, ‘Teenage Wildlife’ is reminiscent of ‘Heroes’, a sprawling, 6+ minute, ever-climbing epic with an assiduous guitar.

For the biggest album of his career, Bowie recruited mega hit-writer Nile Rodgers to produce, explaining “…that I wanted to do something with the kind of warmth that I feel missing…in music generally, and from society”.

Nile Rodgers relates an anecdote describing how Bowie could connect sound and image so well: “He came to my apartment one day and he had a picture of Little Richard in a red suit getting into a red Cadillac. And he said to me, ‘Nile, darling, the record should sound like this!'”

While Bowie didn’t want to write a 1950s rock record, he wanted to embody that genre’s early spirit with something electric. He waxed nostalgic on that juiced energy of the early rock acts. As such, his style from the time took on the simple suit and ties of the early performers with an extra little pizzazz.

The 90s

The 90s were a decade marked by another major reinvention in musical style, transitioning to electronica, techno, and drum-and-bass. These genres rely on electronic instruments and synthesizers to create music with harsh, triggering sounds and often equally triggering themes.

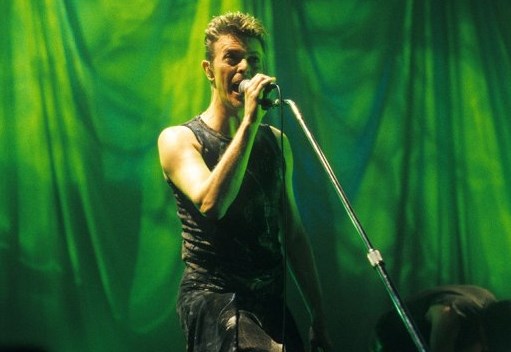

As such, his style for the 90s matched the ‘industrial’ means of making the music itself. Spiked hair, dark colors/bright colors with limited textures, facial hair sculpted into sharp angles.

The Blind Prophet

Following a heart attack in 2004, Bowie would shrink away from the spotlight. He would not perform a concert again and would make scant public appearances. He wouldn’t release new music until 2013’s The Next Day but wouldn’t tour in support of it. Hinting at his decision to stay out of the spotlight, the album art for The Next Day would be a rehash of 1977 Heroes’ album art with the text block completely blocking his face.

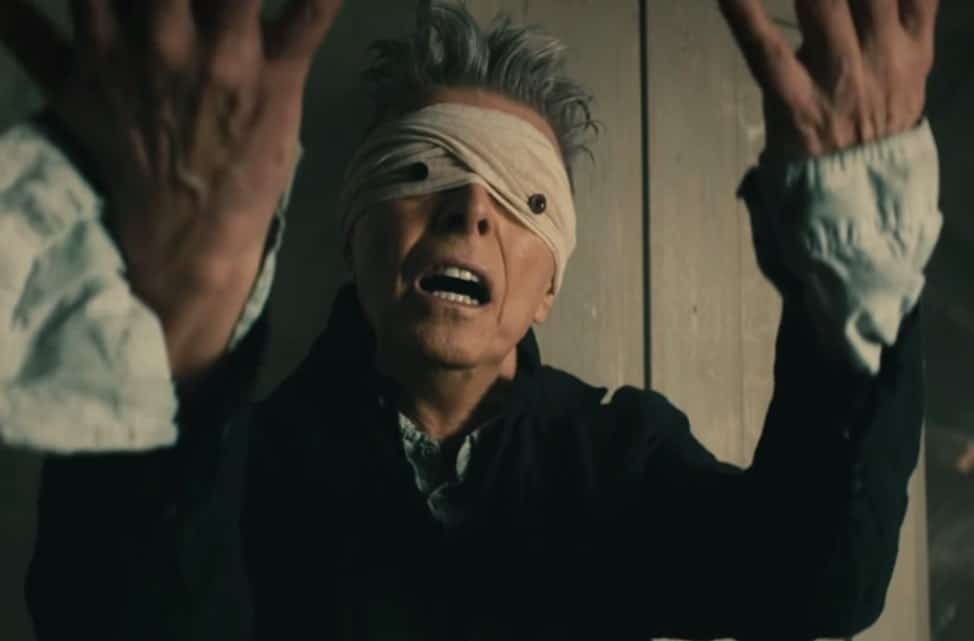

2016’s Blackstar would be David Bowie’s last (before death) release, released on his 69th birthday, two days before his death. David Bowie had planned for Blackstar to be his last, entering the studio for production while undergoing chemotherapy for his battle with terminal liver cancer, even going so far as requesting the musicians on the album to sign NDAs.

But David Bowie would not go gentle into that good night. His last album and its aesthetic would be just as ambitious and well-considered. The album served as Bowie’s own eulogy with themes of mortality, death, rebirth, and loss told through The Blind Prophet. The upper half of The Blind Prophet’s face was wrapped with two small buttons serving as his ‘eyes’ but was no less expressive (thanks to Bowie’s extensive mime/theatre training/career).

The Blind Prophet is a character of uncertainty, arms flailing out in hopes of touching something or coiled, clutching a blanket in fright. He wears anachronistic clothing, hailing to the days when the Earth was still yet to be explored.

FAQ

Answer: While most of his music was centered in the rock genre, David Bowie incorporated many genres, including but not limited to: pop, art pop, glam rock, funk, soul, drum-and-bass, and electronica.

Answer: While David Bowie thought very highly of Warhol, even being the first performer to cover The Velvet Underground (Andy Warhol managed the group and hired them as his house band for his art collective), Andy Warhol didn’t reciprocate the infatuation. Before Bowie had broken through in America, they had met. Ultimately, they were unimpressed with David Bowie and his song (‘Andy Warhol’ from Hunky Dory).

Answer: A scuffle in his teenage years with a classmate and future artistic collaborator George Underwood took a severe turn when Underwood’s fingernail scratched David Bowie’s eye. After months in the hospital, Bowie was left with anisocoria (a differently sized pupil), which changed the appearance of his eyes’ irises.

Conclusion

David Bowie had the courage to reinvent himself and the diligence and artistic talent to make a statement with each of those reinventions. For decades, he proved an inspiration for artists across all media and a trendsetter in the context of cultural movements.

While I understood that David Bowie was a master of rebirth and reinvention, I was still surprised by the extent of the changes and his attentiveness to each in my research for this article. We may never again see a genius of the same caliber as David Bowie.